Provided By GoLegal

By Alicia Koch

16 Nov 2018

As women, we are taught from a very young age to take on many different roles. From daughter to wife to mother, and now, successful bread winner. And along with all those expectations and achievements, many women are faced with internal conflict, gender discrimination and inequality, domestic violence, sexual harassment and varying degrees of male chauvinism.

In fact, I can confidently say that amongst my women colleagues, friends and family, there is not one of us that has not been affected by gender inequality and gender related abuse in the workplace.

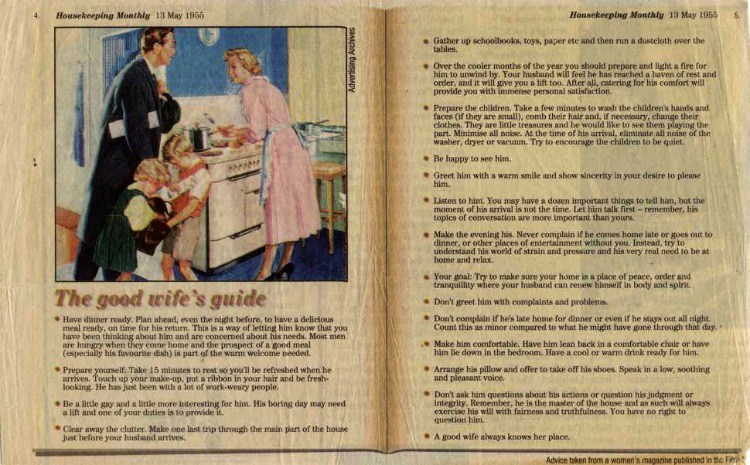

However, whenever discussions around the inequalities faced by female professionals in the workplace come up, our husbands, boyfriends, friends, fathers, brothers, and colleagues, will often playfully invoke images of a happier, simpler time – often humorous, but ostensibly offensive. Times where a woman was taught to be a “Good Wife”; where her place was in the home, and where men, as a general collective were the ones who remained in control.

It’s meant to ease tension through humour. But it doesn’t.

To fairly illustrate the woman’s struggle for equality, it is not only important, but also necessary, to at least touch on some history…

Gender discrimination – then

“Women have historically been associated with inferiority in philosophical, medical and religious traditions. Hellenic philosophical schools, such as Stoicism and Platonism distrusted all that was corporal, favouring instead the spiritual. The hierarchical dichotomy of body versus soul/intellect was seen to parallel the division of the sexes, with women, due to their childbearing functions and menarche, pejoratively associated with corporeality. The mistrust of the flesh extended to mistrust of sexuality; a common antifeminist trope that developed over centuries was the idea of the woman as temptress, someone who tempts the virtuous male from the true ascetic path to wisdom. With the advent of Christianity, the Old Testament figure of Eve came to embody earlier misogynist traditions: Eve, the sinful Woman (Woman because she in fact represents all women) who condemned humanity by corrupting Adam. Moreover, since Eve was born out of Adam’s rib, the link between Woman’s physicality and debt to Man was made more manifest.

Even in medical treatises of the first five centuries AD, women’s inferiority to men was justified by their physiological weaknesses. In Aristotelian physiological tradition, which influenced medieval, early modern and even modern notions of sex and gender, Woman is the imperfect version of Man: she is matter whereas he is form. For the Greek philosopher and medical doctor, Galen (AD 129 – 200), women lacked self-restraint whereas men were characterised by self-control.

These traditions intersected and justified the dominant view that women were physiologically, intellectually and spiritually inferior to men.”

If this is the starting point to the gender equality debate, it leaves little wonder why it has been such a long, hard and unfortunately ongoing uphill battle…

The Woman’s suffrage movement

Whilst globally the women’s suffrage movement was initiated and fought by woman in many countries, it was in the US and UK where as early as 1888 the first international women’s rights organisation was formed, the

International Council of Women (ICW).

In contrast, South Africa has only over the last three or four decades given

women’s role in the history of South Africa any recognition. Previously, the history of women’s political organisation, their struggle for freedom from oppression, for community rights, and, importantly, for gender equality, was largely ignored in history texts. Not only did most of these older books lean heavily towards white political development, but they also focused on the achievements of men (often on their military exploits or leadership ability), virtually leaving women out of South African history altogether.

However, on 9 August 1956 the massive Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria took place. Women throughout the country put their names to petitions and thus indicated anger and frustration at having their freedom of movement restricted by the hated official passes. The bravery of these women (who risked official reprisals including arrest and detention) was the initial step that started the change in the course of history for South Africa women on a massive scale. They were tired of staying at home, powerless to make significant changes to a way of life that discriminated against them primarily because of their race, but also because of their class and their gender.

It seems like heroic initial steps in the right direction, but what has actually changed since then?

Gender discrimination – now

“Some 30% of South Africa’s women (and 18% of its men) have been victims of unwanted sexual advances in the workplace…”

The survey goes on to say that:

“About 57% of women and 47% of men claimed that the unwanted advances came from a workplace peer, while 26% of women reported that a boss or superior was the source of the harassment.”

As recent as 2017, the speaker of the National Assembly, Baleka Mbete, asked this of Parliament:

“Why, despite all our policies and laws to address gender discrimination, do women still suffer such high levels of physical violence and other manifestations of gender discrimination in work and other spheres of life?”

A very good question, and one which our Courts have sought to address in the matters of Adila Chowan vs Associated Motor Holdings (1

st defendant),

Imperial Holdings Limited (2

nd defendant), and its CEO Mark Lamberti (3

rddefendant); as well as in the Rustenburg Platinum Mines labour court issue. Additionally, an issue that has received significant attention as a result of Grant Thornton’s “Sex Pest Controversy”.

“The ground-breaking court judgment held Imperial Holdings Limited and its CEO Mark Lamberti jointly and severally liable for impairing the dignity of Associated Motor Holdings’ financial manager Adila Chowan, and provides much needed hope for victims of discrimination in the workplace.”

“Workplace discrimination in South Africa is a matter of public interest as correctly pointed out in the court judgment against Imperial Holdings and its CEO. This means that listed and state owned companies are duty bound to consult stakeholders that represent the interests of race, gender and disability to eliminate unfair discrimination in the workplace and to advance affirmative action. The Companies Act and its regulations provide leverage for civil society to compel companies to adopt alternative dispute resolution policy. Adoption of such policy would encourage employees who are weary of exposing discriminatory practices to be more open. Companies are more likely to consider adopting this kind of policy if there is pressure from civil society.”

In the recent Labour Court decision concerning Rustenburg Platinum Mines Limited v UASA obo Pietersen, Judge Edwin Tlhotlhalemaje was left feeling appalled by a decision made by Josias Maake (a commissioner for the CCMA) who reinstated and ordered the back-pay of R576 000 for the Rustenburg Platinum Mines engineering specialist, Steve Pietersen.

Pietersen was fired after an employee reported that for eight years she had been asked for sex at least twice a month by Pietersen – advancements which were consistently rejected by the employee. But it was ultimately the employee’s husband who laid the complaint of sexual harassment against Pietersen (on his wife’s behalf).

Following a preliminary investigation of the allegations, a disciplinary hearing was convened. Pietersen was found guilty and was dismissed. He then subsequently took the issue to the CCMA, supported in his endeavours by the trade union, UASA

During the CCMA proceedings the employee explained that she had not reported the harassment for a period of roughly seven years, as she had feared further victimisation and was concerned that the truth would hurt the harasser’s wife – whom she regarded as a close friend.

The Commissioner (Maake) took issue with the fact that the employee had not clearly and unambiguously said ‘no’ to the advances and concluded that Pietersen’s advancements did not amount to sexual harassment – “At best‚ they appear to depict a love proposal‚” Maake said. “Surely there can never be anything untoward for an employee to be attracted to a co-employee … and to accordingly propose love.”

Importantly, Judge Tlhotlhalemaje stated that nowhere in the Code of Good Practice on Sexual Harassment does it require the accused employee to have been aware that their conduct was unwanted and offensive to the complainant in order for the conduct to constitute sexual harassment.

Judge Tlhotlhalemaje scrapped Maake’s reinstatement of Pietersen‚ as well as his order that Pietersen should get R576‚000 in back pay. The Judge further ordered UASA to pay Rustenburg Platinum Mines’ costs in the labour court case as “It should have been apparent to [the union] that the commissioner’s award was indefensible‚”.

This matter is extremely important as it highlights the fact that it is no longer a defence for an alleged perpetrator to claim ignorance of their advances being unwelcome in order for such action to constitute sexual harassment. The ruling is also in line with global standards on sexual harassment.

Grant Thornton

Accounting and Advisory organisation, Grant Thornton, have been embroiled in what is being dubbed as the ‘

Sex Pest Controversy” which officially began in March 2018 when one of its erstwhile directors, Nerisha Singh let the proverbial cat of the bag during the Eusebius McKaiser Show. She recounted the trauma she endured following sexual harassment at the hands of Grant Thornton Johannesburg’s Head of Forensics, Vernon Naidoo. She also relayed the resultant helplessness felt thereafter due to the lack of a redressal system for such cases.

After Naidoo was exposed and handed in his resignation, further reports emerged that Grant Thornton had continued to conduct limited business with him to conclude the contracts that he had been active on. The firm’s perceived response to the allegations caused as much outrage as the allegations themselves with matters taking a turn for the worst when it arose that Singh was dismissed from the firm after speaking out on the Eusebius McKaiser Show. As a result, Singh decided to pursue legal action against the firm, the aim of which was to get Grant Thornton Johannesburg to take accountability for, amongst other things, the sexual harassment suffered, victimisation, failure to protect her, as well as responsibility for her unfair dismissal.

In response to these reports, Grant Thornton Johannesburg’s CEO Paul Badrick issued a public apology wherein he apologised to the employees who were victims of the sexual harassment, expressing his deepest regret, and acknowledging that it was a mistake to allow Naidoo to continue performing limited services after leaving the firm. He also swiftly confirmed that Grant Thornton had in fact, cut all ties with Naidoo. Lastly, Badrick stated that the grievances and culture of Grant Thornton Johannesburg would need to be investigated by independent third parties, adding that Grant Thornton International Limited (GTIL) would be one of the parties to do so. He said he would also welcome an investigation by the Commission for Gender Equality.

In a surprising and ironic twist of fate, Badrick voluntarily stepped aside in June 2018 when sexual harassment allegations against him came to light during the internal investigation by GTIL. Whilst these allegations against Badrick were made in 2015, no formal complaints were made until the GTIL investigation was concluded. GTIL stated that “the Johannesburg firm’s management failed, in these instances, to address inappropriate behaviours that were at odds with what we expect from our senior leaders.”

As a result of the above, Grant Thornton Johannesburg approached attorneys Norton Rose Fulbright (NRF) to conduct independent legal reviews of the alleged sexual harassment. NRF’s independent review found that only one complainant had merit and Badrick was cleared of all sexual harassment allegations against him at the end of August 2018, swiftly returning to work as CEO thereafter.

Serena Ho, the chairperson of the governing board at Grant Thornton Johannesburg, confirmed that the firm had now put in place structured policies and procedures for dealing with sexual harassment complaints.

An amicable settlement was also reached between Grant Thornton and Singh with Singh’s attorney Natasha Moni confirming that “the settlement is meaningful to Nerisha Singh.” As a result, Singh’s complaint with the Commission for Gender Equality has also been withdrawn.

Grant Thornton’s Sex Pest Controversy has been included here as it adds another dimension to the ongoing debate in South Africa around gender diversity in the workplace. Currently, a large portion of firms in the country don’t have women in senior roles and this simply represents yet another barrier that women regularly face to thriving in the workplace.

The global reality of the situation is startling

Early in 2018, at the Commission for the Status of Woman[1] held in New York, almost 20 000 people in 28 countries were asked to rate their concerns about a number of gender and equality issues in the study, “

Perceptions are not reality… and we’re not as close to equality as we think”– a special Ipsos survey conducted to explore attitudes and misperceptions around the “Press for Progress” themes”.

As the only African country participating in the study, the South African participants said that the most important issues facing women and girls in South Africa are sexual violence, domestic abuse and access to sanitary towels. In fact, across the study (and in global terms), sexual harassment is seen as the most important issue facing women today.

It is also interesting to note that as an example of perception vs reality in Great Britain and the US, both men and woman are “extremely optimistic” when it comes to how long it will take for men and women to have equal pay in their country. At the current rates of progress, in the US, equal pay will only be achieved by 2059, while the perception is that it will be achieved by 2028 on average. In the UK, equal pay will only be achieved by 2117, while perception is that it will be achieved by 2035.

In both cases, far off.

“We also asked people how many of the top 500 corporations have women as CEOs. Everybody overestimated the number… in fact only 3% of women are in top positions, this means only three out of every 100 is a female, and that is what we mean with, ‘perceptions are not reality…”

South Africa and the fight against Gender Discrimination

“Economic empowerment remains one of the most crucial factors to achieving gender equality. In the latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) released by Stats SA, South Africa’s unemployment rate dropped to 26.7% in the fourth quarter of 2017 from 27.7% in the previous third quarter. The slight decline is encouraging, but the QLFS highlighted that women, and particularly young women, are still more likely than men to be unemployed…”

“According to the second quarter 2017 QLFS, women fill 44% of all skilled posts in the country. These include managers, professionals and technicians. This figure has not shifted since 2002”.

To what extent does the South African Constitution and other legislation protect women against discrimination and inequality?

Section 9 of the

Constitution of South Africa guarantees equality before the law and freedom from discrimination. This equality right is the first right listed in the Bill of Rights. It prohibits both discrimination by the government and discrimination by private persons:

“Section 9 Equality

(1) Everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law.

(2) Equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms. To promote the achievement of equality, legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken.

(3) The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.

(4) No person may unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds in terms of subsection (3). National legislation must be enacted to prevent or prohibit unfair discrimination.

(5) Discrimination on one or more of the grounds listed in subsection (3) is unfair unless it is established that the discrimination is fair.”

Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act

PEPUDA is a comprehensive South African anti-discrimination law which prohibits unfair discrimination by the government and by private organisations and individuals, and forbids hate speech and harassment. The act specifically lists race, gender, pregnancy, family responsibility or status, marital status, ethnic or social origin, HIV/AIDS status, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth as “prohibited grounds” for discrimination, but also contains criteria that courts may apply to determine which other characteristics are prohibited grounds. Employment discrimination is excluded from the ambit of the act because it is addressed by the Employment Equity Act, 1998. The act establishes the divisions of the High Court and designated Magistrates’ Courts as “Equality Courts” to hear complaints of discrimination, hate speech and harassment.

Furthermore, PEPUDA is mandated by section 9(4) of the Constitution, and thus enjoys special constitutional status. Significantly, the Act recognizes the need to address systemic discrimination and specifically aims at the ‘eradication of social and economic inequalities’. In terms of section 13 of PEPUDA, discrimination based on the prohibited ground of gender is considered unfair, unless it is established that the discrimination is fair. Section 8 of PEPUDA stipulates that no person may unfairly discriminate against any person on the ground of gender, and goes on to list various prohibited forms of gender-based discrimination.

Employment Equity Act

The purpose of the Employment Equity Act (EEA) is to achieve equity in the workplace. This is attempted by promoting equal opportunity and fair treatment in employment through elimination of unfair discrimination and implementing affirmative action measures. The aim is to specifically redress the disadvantages in employment experienced by designated groups, in order to ensure equitable representation in all occupational categories and levels in the workforce.

Key laws protecting women in the workplace

“Protection against dismissal – in terms of the Labour Relations Act, a dismissal is automatically unfair if the employee is dismissed because of her pregnancy, intended pregnancy or a reason related to her pregnancy. A dismissal that is found to be automatically unfair can attract an order of reinstatement or compensation up to 24 months’ salary.

Protection against unfair discrimination – the EEA protects employees from unfair discrimination on listed grounds which include gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, family responsibility or on any other arbitrary grounds.

Equal pay protection – the EEA was recently amended to introduce theequal pay for work of equal value principle (equal pay principle). In terms of the amendment, a difference in terms and conditions of employment between employees of the same employer performing the same or substantially the same work or work of equal value that is based directly or indirectly on any one or more of the listed grounds or on any other arbitrary ground, is unfair discrimination. A Code of Good Practice on equal pay for work of equal value states that the equal pay principle “addresses a specific aspect of workplace discrimination and the undervaluing of work on the basis of a listed or any other arbitrary ground…” As stated above, the listed grounds include gender and sex.

Maternity leave protection – in terms of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA), an employee has a right to at least four consecutive months’ unpaid maternity leave. The Unemployment Insurance Act provides for payment of maternity benefits.

Protection before and after birth – the BCEA also provides protection to employees before and after the birth of a child. In terms of s26 (1) of the BCEA, “no employer may require or permit a pregnant employee or an employee who is nursing her child to perform work that is hazardous to her health or the health of her child.” A Code of Good Practice on the protection of employees during pregnancy and after the birth of child has been issued in terms of the BCEA. The Code recognises that many women return to work while breast-feeding and provides guidelines for employers. It guides employers on how to assess and control risks to the health and safety of pregnant and breast-feeding employees and provides a non-exhaustive list of hazards to pregnant and breast-feeding employees recommending steps to control or prevent those risks.

Family responsibility leave – subject to certain requirements, Section 27 of the BCEA grants employees three days paid leave which an employee can take when the employee’s child is born or sick, or on the death of the employee’s child, adopted child, spouse, life partner, parent, sibling or grandchild”.

What effect do those laws actually have on the lives of everyday people?

An employee who has been unfairly discriminated against, as set out in Sections 5 – 10 of the Employment Equity Act, may refer the dispute (which specifically excludes a dispute about an unfair dismissal) in writing to the CCMA within six months after the act or omission that allegedly constituted the unfair discrimination has taken place. If the dispute remains unresolved after conciliation, the employee may refer the dispute to the Labour Court for adjudication, or they may refer the dispute to arbitration if the employee alleges unfair discrimination on the grounds of sexual discrimination.

In addition to the above, if you have been the victim of gender discrimination you can, at any stage, direct your complaint to the Commission for Gender Equality which is tasked with investigating gender related complaints (your complaints can even be done online). Once an investigation/legal officer is appointed to your case, they will discuss what steps will be taken and what the possible outcomes will be.

Who bears the onus of proof?

Section 11 (1) of the EEA provides that if unfair discrimination is alleged on a ground listed in section 6 (1), the employer against whom the allegation is made must prove, on a balance of probabilities, that such discrimination:

- did not take place as alleged; or

- is rational and not unfair or is otherwise justifiable.

Subsection 2 provides that if unfair discrimination is alleged on an arbitrary ground, the complainant must prove, on a balance of probabilities, that:

- the conduct complained of is not rational;

- the conduct complained of amounts to discrimination, and

- the discrimination is unfair.

Remedies for Unfair Discrimination Disputes

If the CCMA, the Labour Court, or Arbitrator decide that an employee has been unfairly discriminated against, the Court/CCMA/Arbitrator may make any appropriate order/arbitration award, including:

- the payment of compensation by the employer to that employee;

- the payment of damages by the employer to that employee;

- an order/award directing the employer to take steps to prevent the unfair discrimination or a similar practice from occurring in the future in respect of other employees.

A sober reminder

“Gender inequality in South Africa remains rife. Substantive inequality is reflected at both a broad, structural, societal level, and in instances of direct discrimination, as is regularly encountered in the workplace. Systemic inequalities relating to the sexual division of labour, and the inaccessibility of other streams of income, resources, land and social services such as education, continue to prejudice women and gender minorities. A holistic approach is needed to combat gender inequalities in whichever sphere of society and the economy these may manifest. In order to effect structural change in an effort to achieve substantive gender equality, it is similarly important for lawmakers to proclaim the commencement of Chapter 5 of PEPUDA, which recognises that the duty to promote equality rests on all those who inhabit South Africa”.

Whilst this article is not intended as a doom and gloom piece, it does recognize beyond a shadow of a doubt, the harsh reality that gender discrimination is still rampant both in South Africa and around the world. With equal pay, sexual harassment and abuse still being so high on the list of concerns, many women wonder with increasing desperation – when will the tide start turning?

It seems appropriate to thus end this article with the following “I do not wish women to have power over men; but over themselves” Mary Shelley.

And that’s really the crux isn’t it? Gender equality is not about disliking men or wanting dominion over them. It is simply about wanting to be treated fairly and equally, and to have our concerns, our ideas and ourselves, taken seriously.

Useful organisation’s and commissions to address any issue of gender discrimination complaints to: